The Importance Of Spare Capacity – Why Your Spine Needs A Safety Margin

What if your back pain isn’t just from one bad movement — but from constantly living on the edge of your spine’s limits? This is

Tendinopathy is a condition that affects tendons, the fibrous tissue that connects muscle to bone. Tendons are designed to withstand repetitive stress and movement, but over time, they can become damaged, leading to pain, inflammation, and weakness.

Tendinopathy (used to be referred to as Tendinitis) is an umbrella term used to describe clinical conditions associated with overload in and around tendons. The old-school Tendinitis, which was based on the theory of ‘inflammation’ (‘itis = inflammation) is no longer used as more recent evidence has shown that at a cellular level the tendon cells of a pathological tendon are actually not ‘inflamed’ per se. Histological (cell analysis) samples of chronically painful tendons were actually found to not have inflammatory cells present (Khan, Cook, Bonar et al., 1999).

There are two types of tendinopathy: acute and chronic. Acute tendinopathy is caused by a sudden injury, such as sprain or strain. Chronic tendinopathy on the other hand, is caused by repetitive stress on the tendon over time. The pathophysiology of tendinopathy is complex and multifactorial, but it is generally thought to involve a combination of mechanical, biological, and biochemical factors.

One of the primary factors that can lead to tendinopathy is repetitive or excessive loading of the tendon. This can occur with activities such as running, jumping, or throwing, as well as with vocational activities that involve repetitive motions or heavy lifting. Over time, this repetitive loading can cause microscopic damage to the tendon, leading to inflammation and degeneration.

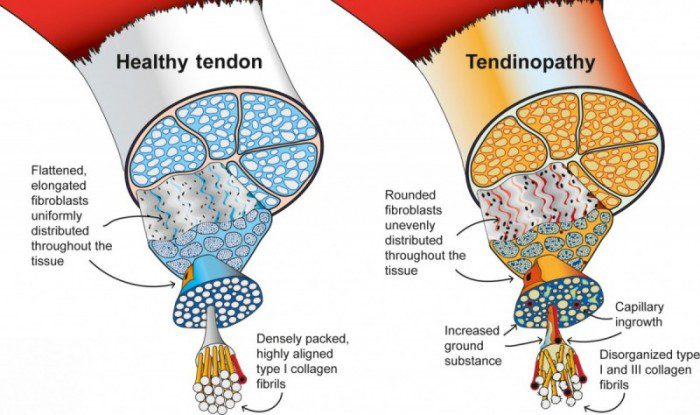

Tendons are made up of specialized cells called tenocytes, which are responsible for maintaining the structure and function of the tendon. In tendinopathy, there is a disruption in the normal balance between tenocyte production and turnover, which can lead to the accumulation of abnormal cells and the breakdown of healthy tissue. In addition, tendinopathy is associated with changes in the extracellular matrix, which is the complex network of proteins and other molecules that provide the structural support for the tendon.

Several different biochemical factors have been implicated in the pathophysiology of tendinopathy, including oxidative stress, inflammation, and the accumulation of metabolic waste products. Oxidative stress occurs when there is an imbalance between the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the body’s ability to neutralize them. This can lead to damage to the cells and tissues of the tendon. Inflammation is also a key factor in tendinopathy, as it can lead to the release of cytokines and other mediators that can cause further damage to the tendon. Finally, the accumulation of metabolic waste products, such as lactate and other by-products of cellular metabolism, can also contribute to the development of tendinopathy.

Tendinopathy commonly occurs in:

Symptoms of tendinopathy include;

To better understand tendinopathy, there is a three-stage continuum of tendinopathy is a model that describes the progressive stages of tendon injury and degeneration (Cook & Pudram, 2009). They are;

Stage 1: Reactive Tendinopathy

In the first stage, the tendon becomes inflamed in response to overuse or injury. This is known as reactive tendinopathy, and it is characterized by pain and swelling in the affected area. The tendon may also be tender to the touch, and there may be some loss of strength or range of motion. At this stage, the tendon is still able to heal and recover if appropriate measures are taken to manage the inflammation and promote healing.

Stage 2: Tendon Dysrepair

If the reactive tendinopathy is not managed properly, it can progress to the second stage, known as tendon dysrepair. At this stage, the tendon becomes more degenerated, and there may be an increase in the number of cells involved in the healing process. The tendon may also develop disorganized collagen fibres and other structural changes that can weaken the tissue. This stage is characterized by persistent pain and loss of function, and it may be more difficult to treat than the earlier stages.

Stage 3: Degenerative Tendinopathy

The final stage of tendinopathy is degenerative tendinopathy, which is characterized by extensive structural damage to the tendon. The tendon may become thickened and nodular, and there may be areas of calcification or other degenerative changes. At this stage, the rehabilitation is more prolonged and may require interventional assistance (like PRP injections or similar) to assist in the recover process.

Treatment for tendinopathy depends on the severity of the condition and the individual’s symptoms. In most cases, conservative treatment options such as physio or occupational therapy, load management and over the counter pain medication can be effective in managing symptoms. In some cases, a combination of these treatments may be necessary.

Initially, load management and symptom management are the main focus. This may include reducing the overall amount of activity/stress you are placing on the tendon – to clarify, we don’t mean completely stop using the tendon and rest, in fact loading the tendon is one of the most crucial factors in rehabilitation tendon issues. BUT it needs to be the correct amount of load at the correct time.

Therapy can help to strengthen the muscles surrounding the affected tendon, which can help to alleviate pain and improve function. This may include exercises to lengthen and strengthen the affected muscle and tendon, to improve the capacity of the tendon tissue to tolerate load.

For example, in the initially stages of rehab, we tend to use isometric exercises which is when the muscles contract and generate force without any movement of the joints. In other words, the length of the muscle remains the same during the exercise, and there is no visible movement of the body or limb being exercised.

References:

Khan KM, Cook JL, Bonar F, et al. Histopathology of common overuse tendon conditions: update and implications for clinical management. Sports Med1999;27:393–408.[CrossRef][Medline][Web of Science]

Cook JL, Purdam CR Is tendon pathology a continuum? A pathology model to explain the clinical presentation of load-induced tendinopathyBritish Journal of Sports Medicine 2009;43:409-416.

What if your back pain isn’t just from one bad movement — but from constantly living on the edge of your spine’s limits? This is

One of the most overlooked causes of persistent low back pain is how we move during everyday tasks. Simple activities like bending, sitting, getting out of a car, or

If you’ve been told your back pain is “non-specific” or has “no clear cause,” you’re not alone. Up to 85% of people with low back