Facet joint – mediated low back pain is one of the most common contributors to persistent back pain, yet it’s frequently misunderstood or oversimplified. This page explains what facet joint pain actually is, how it differs from disc-related pain, why it occurs, and how identifying the underlying movement and loading issues is key to recovery.

In this video, we explain how facet joints work, why they become painful, and why treating facet pain effectively requires more than just addressing the painful area itself.

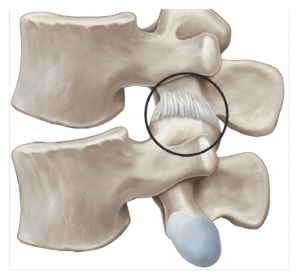

Facet joints are small paired joints located at the back of each spinal segment. In the lumbar spine, they help guide movement, control rotation, and provide stability while allowing bending and extension.

Each facet joint is lined with cartilage and surrounded by a joint capsule, similar to other synovial joints in the body. When functioning well, facet joints share load with the discs and surrounding muscles during everyday movement.

Problems arise when load distribution becomes uneven or when certain movements repeatedly stress the joints beyond their tolerance.

Facet joint–mediated low back pain occurs when one or more facet joints become sensitised or irritated and begin contributing to pain. This can happen due to: →

Importantly, facet joint pain does not mean the joint is “damaged beyond repair.”

In many cases, it reflects mechanical sensitivity, not structural failure.

Although both can cause low back pain, facet and disc pain often behave differently.

Facet joint pain commonly:

Feels worse with extension (arching backward)

Is aggravated by prolonged standing or walking

Feels stiff or “locked” rather than sharp

Improves slightly with flexion or sitting

Is more localised to one side of the lower back

Disc-related pain more commonly:

Is aggravated by flexion or sitting

May refer into the leg

Is sensitive to sustained loading

Understanding this distinction is critical — because treatment strategies differ.

Facet joints rarely become painful in isolation. Most cases involve changes in how load is shared through the spine.

Facet pain is usually a load-management issue, not a joint-wear issue.

Facet joint pain cannot be accurately diagnosed through scans alone. At Perth Injury & Pain Clinic, assessment focuses on how your spine behaves under load — not just what imaging shows.

Our goal is to identify why the facet joint is being overloaded and what needs to change to reduce irritation and restore tolerance.

Facet joint–mediated pain tends to follow specific mechanical patterns. We carefully identify movements, postures, and activities that increase symptoms, as well as those that reduce pain.

Understanding this pattern helps confirm whether the facet joint is contributing and guides which movements should be modified — temporarily — during rehabilitation.

We assess how your spine responds to different types of movement and loading, including:

Extension (arching backward)

Flexion (bending forward)

Compression and sustained postures

Facet-related pain often behaves differently to disc-related pain, and these responses help distinguish between the two.

Facet joints are sensitive to how well individual spinal segments are controlled. We assess whether certain segments move excessively, stiffen unnecessarily, or lack coordinated support from surrounding muscles.

Poor segmental control can increase local joint stress, even during everyday activities.

The hips and spine are designed to share load. When hip mobility is reduced, the lumbar spine — particularly the facet joints — often absorbs more extension and rotational stress than it should.

We assess how movement is distributed between the hips and spine to identify overload patterns contributing to facet irritation.

Facet joint pain is commonly associated with poor endurance rather than poor strength. When stabilising muscles fatigue, load shifts toward passive structures like the facet joints.

We assess how well your spinal stabilisers tolerate sustained activity such as standing, walking, or prolonged postures.

Facet joint loading doesn’t only occur in the gym — it happens during daily life. We assess:

Occupational demands

Prolonged standing or walking tolerance

Repetitive postures

Habitual movement strategies

This helps ensure rehabilitation strategies are practical and relevant to your real-world demands.

By combining these findings, we can identify why the facet joint is being overloaded, not just where pain is felt — allowing treatment to target the true driver of symptoms.

Facet joint–mediated pain responds best to strategies that improve load sharing and movement efficiency rather than aggressive stretching or repeated spinal manipulation.

Temporarily modifying movements that repeatedly load the facet joints.

Building fatigue resistance so load doesn’t shift to passive joints.

Allowing the hips to share load and reduce spinal extension stress.

Improving how daily tasks are performed to limit cumulative irritation.

Restoring extension capacity once the spine can tolerate it.

Developing confidence and long-term tolerance rather than fear of movement.

Not reliably. Imaging such as X-rays, CT scans, or MRIs can show changes in the facet joints, but these findings don’t always correlate with pain. Many people have visible changes on scans and experience no symptoms, while others have significant pain with minimal imaging findings. This is why movement-based assessment is often more useful than relying on scans alone.

Prolonged standing can increase extension and compression through the lumbar spine. If spinal endurance is low, load may shift toward the facet joints, increasing irritation and discomfort.

Some exercises can aggravate symptoms if they involve excessive extension or poor load control. However, appropriate exercise is often an important part of recovery when programmed correctly.

Yes. Symptoms often fluctuate depending on activity levels, fatigue, posture, and daily demands. This pattern supports the idea that facet pain is strongly influenced by load and movement, not just structure.

It depends on how your spine responds. Some people find walking aggravates symptoms, particularly if endurance is low or extension is excessive. Others find it helpful. A thorough assessment helps determine how walking fits into your recovery and whether it should be modified or progressed over time.

A detailed assessment looks at how your pain responds to movement, posture, and load. Patterns of aggravation and relief often provide more useful information than imaging alone.

The McGill Method is a comprehensive approach to assessing and managing low back disorders. It focuses on identifying your unique pain triggers and teaching you how to move in ways that reduce stress on the spine. From there, rehabilitation progresses toward building stability, improving hip–spine coordination, and increasing your long-term capacity and resilience.